Contents

Page

Current

Chapter:

8

Punctuation

&

Symbols

Play

TRACK 10

Previous

Chapter

Next

Chapter

rigins

Writing

of

Intro

What

Is

Writing?

Birthplace

of

Writing

Children

of

Egypt

The

Neanderthal Script

Oracle

Bones

Extinct

Scripts

Invented

Writing

Punctuation

&

Symbols

Number

Systems

Lessons

From

Writing

𑁮

Punctuation & Symbols

Punctuation – not as common sense as you might think

So what about punctuation and other symbols used in writing systems? Where do they come from? Well, punctuation marks were not as widespread or standardised in ancient writing systems as they are today (if existent at all!). Like writing itself, they evolved over a long period before becoming accepted conventions. The ancients tended to give preference to oral speech over writing, with written text often only an oratory guide. But without punctuation, a text required a detailed examination before its meaning could be inferred. Therefore, one could not simply read a text out loud at first glance and hope to get the meaning or intonation right. The 2nd century CE writer Aulus Gellius famously refused to read a text aloud for fear of bungling its intended meaning.¹

Many scripts initially had peculiar alternatives for punctuation. For example, the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans sometimes used red ink to mark important text such as headings, instructions or keywords.² Early punctuation marks, meanwhile, mostly served to give oratory cues to the reader, and only later indicated grammatical conventions.³ While many writing systems developed their own indigenous punctuation systems over time, Latin punctuation conventions have now been largely adopted around the world.

← Click image to enlarge

Scriptio continua

Mostancientscriptswerewrittencontinuouslywithnospacesorfullstopsbetweenwordsorsentences. This is commonly referred to as ‘scriptio continua’.⁴ In fact, Chinese and Japanese writing still uses this method, albeit with clearer word distinction due to using logograms. For linear scripts, before word spacing was introduced, inferring word division depended on context and interpretation. Egyptian hieroglyphs gave implicit hints through the use of determinatives, while some scripts occasionally used word separator symbols. Anatolian hieroglyphs used a specific symbol ( ), while most utilised a single stroke e.g. Linear A & B (I), Akkadian and Ugaritic cuneiform (𒁹), and Old Persian cuneiform (𐏐).⁵ Semitic abjads required clearer word separation due to mostly lacking vowels. They achieved this through various means in different periods. Arabic solved the dilemma by indicating whether each letter is an initial, medial or final letter in a word through its cursive typography. Aramaic, Hebrew and Syriac while often being written in scriptio continua sometimes used either spaces or interpuncts as word dividers – usually a mid-dot (·) or colon (:).⁶ ⁷ ⁸ Nowadays, these scripts, like Latin, make use of word spacing. Ethiopic Ge’ez continues to use a colon (:) as an interpunct but is gradually incorporating spaces.⁹

Tip: Hover cursor over image to pause slideshow 👆🏻

↑

Click here to pause slideshow

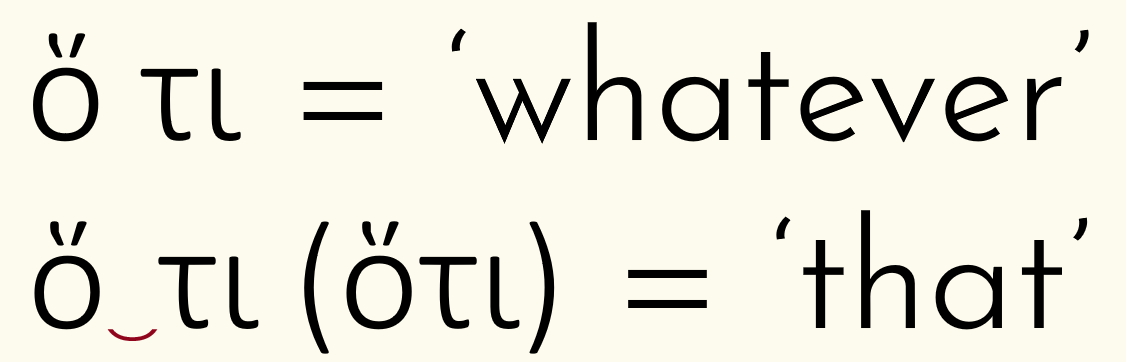

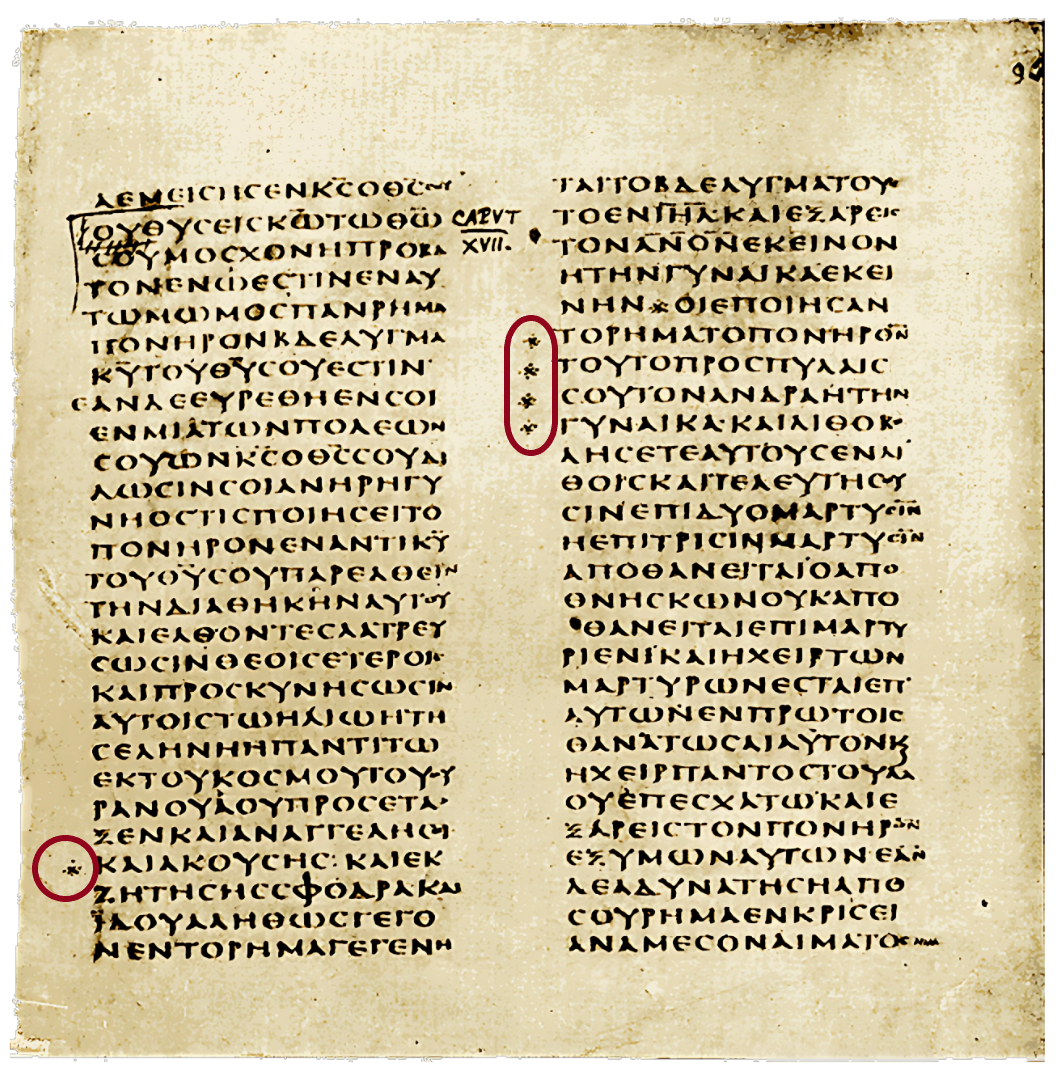

Ancient Greek writers occasionally separated words with mid dot interpuncts (·), but mostly wrote in scriptio continua (as did writers of Greek’s child systems Coptic, Gothic, Glagolitic and Cyrillic).¹⁰ A diastole or hypodiastole () was sometimes used to avoid ambiguity by distinguishing two words that could otherwise be misread as one. Conversely, an enotikon (sometimes called a Greek hyphen) () was sometimes used to indicate that a series of letters should be read as a single word. Paragraphoi ()¹¹, possibly derived from the Greek letter gamma (Γ), could also be used to mark a division in a text. To separate paragraphs, a blank line was often utilised.¹²

Space cadets

Classical Latin was also mostly written in scriptio continua, and indeed entirely in majuscule (upper-case script). However, influenced by early Greek writing, they did make use of interpuncts to separate words for around six centuries. This was usually either a single centred dot (·) or a small triangle (). But this convention was mostly discarded by the 2nd century CE with a return to favour of scriptio continua.¹³

There were also no spaces between paragraphs in Latin at this point. To indicate the start of a new paragraph, the first letter or two of a new paragraph were instead enlarged and projected into the margin (often very ornately). Influenced by the Greek paragraphos, a large C standing for capitulum ('little head') was also later used to indicate the start of a paragraph. This was later stylised as and then before coming to resemble the so-called pilcrow (¶) which is still used in some office software to denote paragraph separation.¹⁴ Pilcrow had to compete with other rival symbols as a paragraph marker in the Middle Ages. The fleuron symbol (also known as a hedera) (❦), resembling a grape leaf, had also been used ornamentally in Greek and Latin, but the pilcrow eventually won favour among scribes.¹⁵

It was Irish and Anglo-Saxon scribes who later formulated the concept of using spaces as a word divider for Greek and Latin in the 7th century CE, using them as visual aids to pronunciation. Latin and Greek were after all not their first language. This convention gained wide usage in Europe by the 11th century and mostly standardised by the 17th century, although minor slight variations continued to evolve. For example, in English, double spacing between sentences used to be the norm until it was replaced by single spacing after the introduction of the computer and digital typography.¹⁶ While Chinese and Japanese continue to use scriptio continua, many non-European scripts have also adopted or started to adopt spacing, including Arabic, Hebrew, Korean Hangul, Ge’ez and most Brahmic scripts.¹⁷

Making a point

So how did the ancients separate clauses and sentences before commas, full stops and upper-lower case distinction? The story begins in around the 3rd c. BCE with a system attributed to Aristophanes of Byzantium, head of the Library of Alexandria. His system directed readers by indicating oratory pauses or breaths. A low dot (.) which he called a ‘kolon’ (‘segment’ or ‘clause’) represented a medium pause, a mid-dot (·) which he called a ‘komma’ (“I cut”) represented a short pause (much like the modern comma), and a high dot (˙) which he called a ‘periodos’ (“going around”) represented a long pause (usually with the completion of a thought).¹⁸ ¹⁹

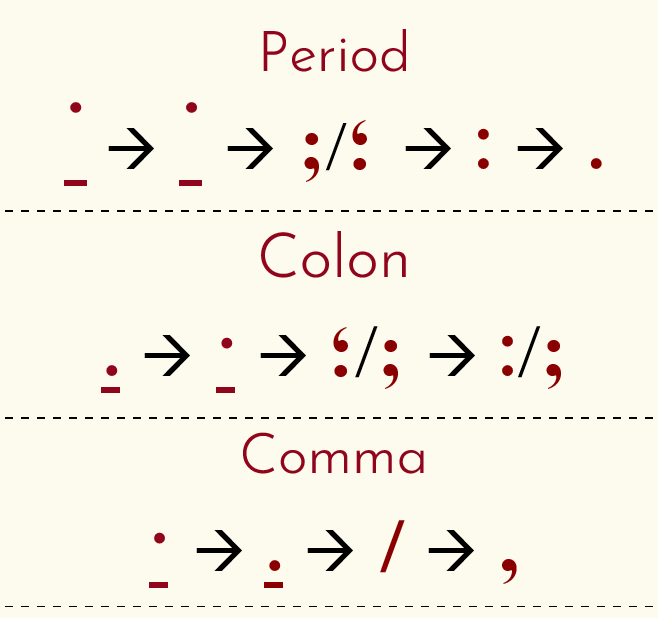

Latin speakers were reluctant to adopt Aristophanes’ system, and the concept had all but died out within several centuries. That was until Latin re-introduced a spin-off version of it in the Middle Ages, testified in Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae written in the 6th century CE. In this version, rather than simply indicating oratory pauses, the dots were used as grammatical markers. The high dot (period) retained its role as marking a complete thought, but the low and mid-dots (perhaps more logically) switched positions, with the respective names following the symbols’ roles rather than their positions. Thus, the low dot took the role of the comma (later referred to as a ‘punctus’), representing a short pause, while the mid-dot took the role of the colon, representing a completed thought, but with something extra to say.²⁰

The system described by Isodore was widespread in Europe by the 9th century, but was complicated due to the introduction of miniscule script which made discerning punctuation difficult due to the smaller letter heights. Thus, punctuation evolved again in the following centuries and new marks emerged, for example the ‘punctus elevatus’ (⸵) (used for a medium pause)²¹ and the ‘punctus versus’ (;) (marking the end of a sentence).²² The punctus elevatus was the inspiration for the later colon symbol (:) which was used to mark the end of a sentence in place of the high dot period, but eventually the top dot was dropped and the bottom dot (.) took over the role of the period. But the colon symbol wasn’t done yet! Instead, it changed careers, taking the role of the modern colon (for uses such as introducing lists, quotes, etc.). The punctus versus, meanwhile, eventually took on the role of the modern semi-colon (;) representing a medium pause rather than the end of a sentence. The low dot comma was eventually replaced with a forward slash (/) or ‘virgula’, which then simplified into the smaller, modern ‘tailed dot’ comma (,).²³ These conventions were mostly standardised in Latin by the 16th century thanks to the printing press and printers such as Aldus Manutius.²⁴

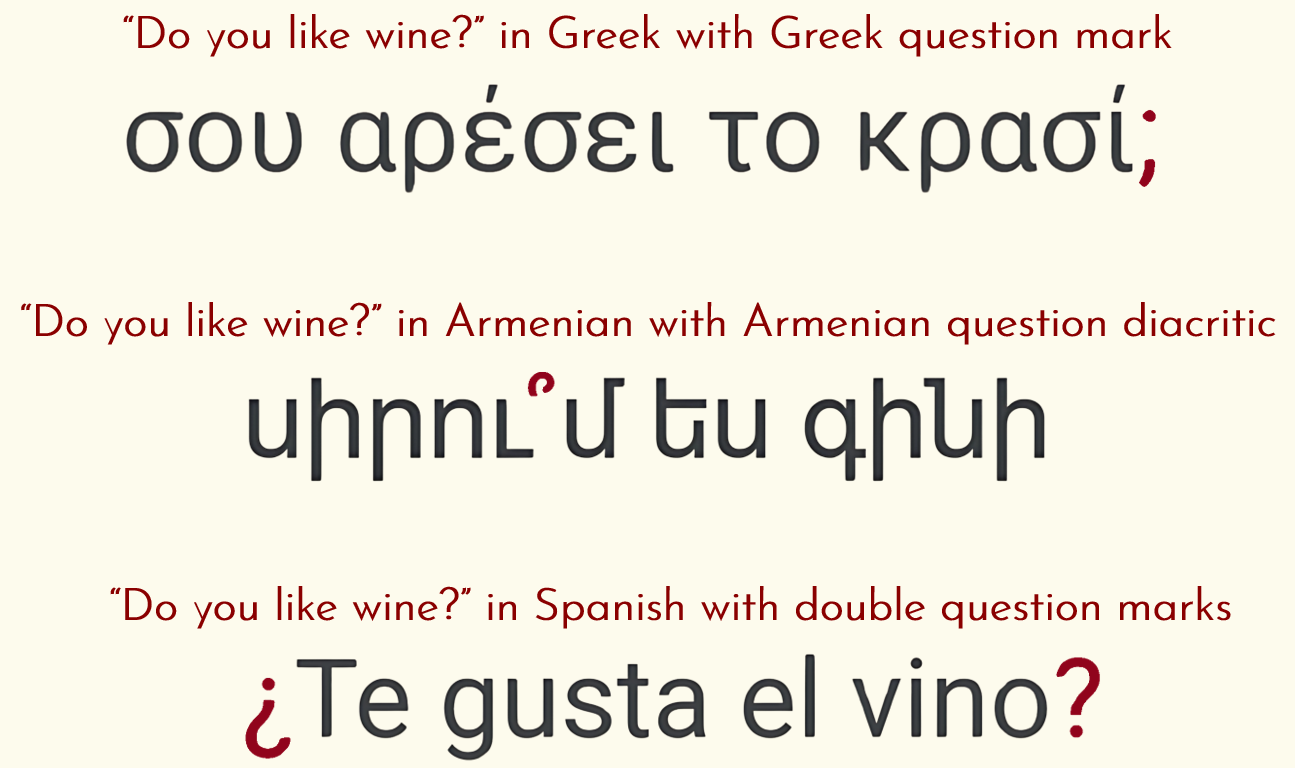

Greek punctuation marks on the other hand, evolved in a very different way. To this day, Greek uses the mid-dot (·) with the function of the Latin colon (:) and uses the Latin semi-colon (;) with the function of a question mark. Latin and Greek do today, however, share the same comma symbol (,). French is also noteworthy for placing a space between punctuation marks and the surrounding letters (« C’est vrai, non ? »).²⁵

Greek, like many scripts, has begun adopting more Latin punctuation conventions since the introduction of computers and the global domination of English and Latin script. The Latin colon, for example, is often used instead of the mid-dot due to its omission from the Greek keyboard layout.²⁶ Punctuation conventions do, therefore, continue to evolve even into the modern era. Sadly (or not, depending on your view), the Latin semi-colon has suffered a fall from grace in the last few centuries; its use dropping by 70% between 1800 and 2000.²⁷

The Question Mark

In Ancient Greek and Classical Latin, like in many languages, questions were understood, not by punctuation marks, but from context and word order. Other languages made use of interrogative (or question) particles to indicate a question. For example, Classical Chinese used question particles 嗎 (ma) or 呢 (ne), Classical Arabic هل (hal), Korean 까 (kka) or 나 (na), and Cyrillic ли (li).

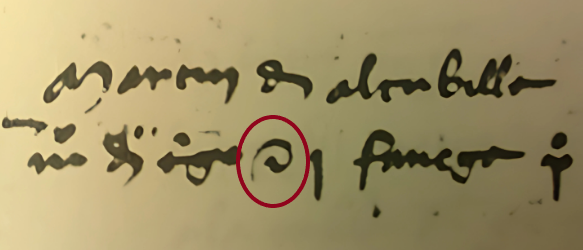

The development of the question mark in Latin is largely a mystery, but there are several theories that attempt to explain it. One common one is that in Medieval Latin, questions were sometimes indicated by writing the word quaestio (question) at the end. This was sometimes abbreviated as Q (majuscule) or qo (minuscule). Either the abbreviated Q came to resemble the question mark over time or the q and o from the minuscule abbreviation were rearranged so that the q lay above the o. But the questio origin theory doesn’t offer much in the way of evidence.

A much stronger theory is that the ‘punctus interrogativus’, a “lightning flash-like” or tilde-like symbol over a dot () first attributed to the scholar Alcuin of York in the 8th century CE, is the precursor.²⁸ Originally denoting an upward intonation, it came to take the shape of the question mark over time and was eventually standardised as an interrogative symbol.²⁹

Whatever the real story, different languages adopted the modern Latin question mark at different times, and by the 20th century, it was more or less a global standard. Exceptions to this include modern Greek, which uses a semi-colon (;), standardised around the same time as the Latin question mark, Ge’ez which uses three dots (፧), and Armenian which uses the diacritic mark () placed above the stressed vowel of the question word.³⁰ Spanish is also notable for its use of double question marks, one inverted opening and one regular closing at the end (¿…?).

The Exclamation Mark

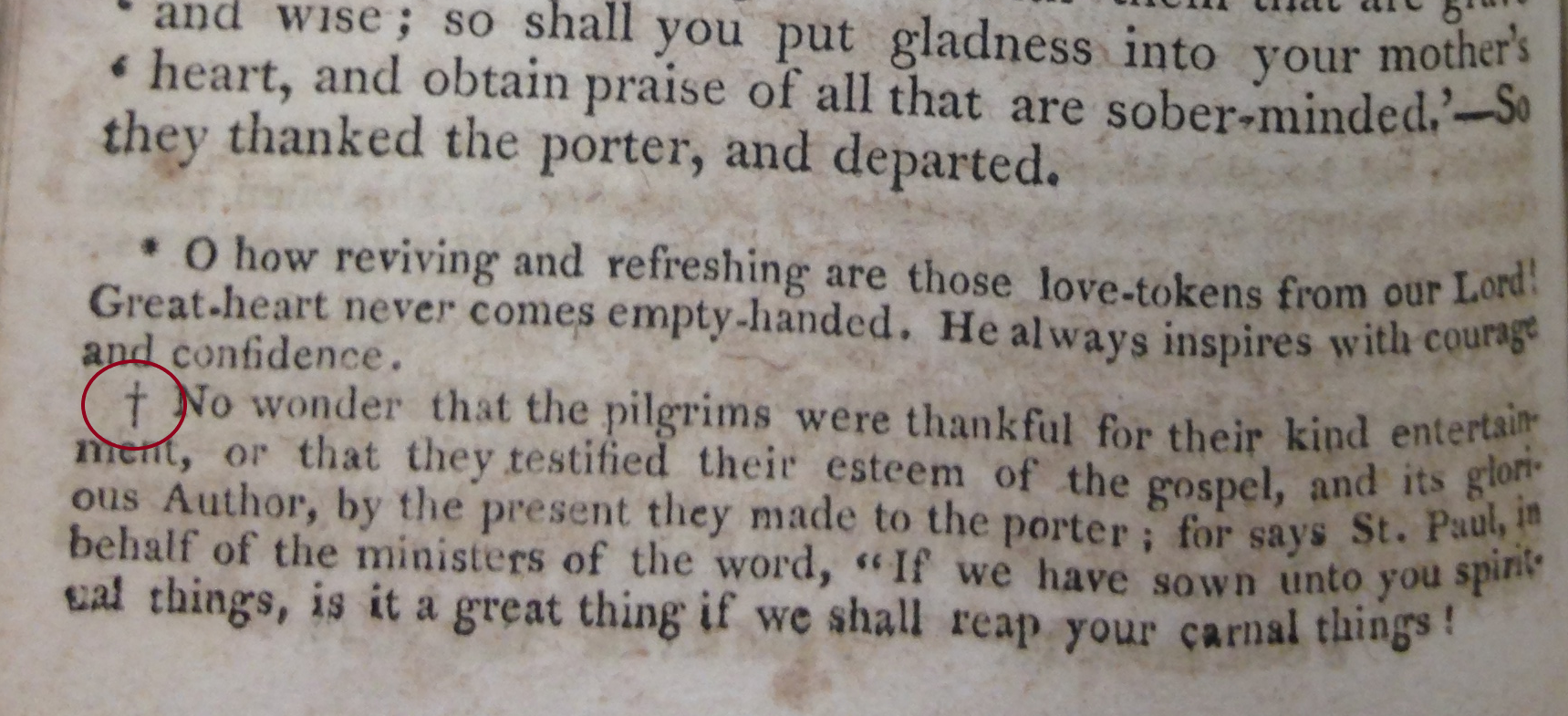

Ancient Greek and Classical Latin writing relied on word choice and context to express emotion rather than punctuation marks. It is in the Latin texts of Medieval writers that we see the first use of the exclamation mark. But like the question mark, its origin is unclear. One theory is that it derives from the obelus (literally “sharpened stick”) symbol which had many different variants such as the (modern) division sign (÷) and the dagger mark (). It was used to highlight a passage or to indicate a footnote. Another, more popular, theory is that it derives from the Latin word ‘io’ which means something along the lines of ‘hurrah’. It is theorised that over time the I began to be placed above the O, giving the modern exclamation mark (!). But there is also scanty evidence for this theory.³¹

The hyphen derives from the enotikon () which was used by Greek scribes to clarify that certain letters belonged to the same word (opposite of the hypodiastole). After the development of word spacing in the Middle Ages, many scribes starting making costly mistakes by accidentally separating words that belonged as one. Because of this, the enotikon was put back into service to show that the separated words should be read as one. When the printing press was invented, it wasn’t possible to print sublinear text, so the enotikon was printed instead as a middle line (-) which is our modern hyphen. Today it is mostly used for compound words, although its use is seeing a steady decline.³²

Apostrophe

Another punctuation sign that emerged in the Middle Ages was the apostrophe (‘), perhaps inspired by the Greek hypodiastole. It was introduced into Medieval Latin script to indicate vowel elision, before widening its usage to things such as word contractions and possessives.³³

Ellipsis

Like the apostrophe, the ellipsis (…) emerged in the Middle Ages, as a series of short dashes used to denote omissions in quoted texts. The dashes gradually became shorter and shorter until they resembled dots. The ellipsis, like many punctuation marks, was standardised with the emergence of the printing press.³⁴

Brackets

Brackets started their life in the 16th century with the use of angled brackets, or chevrons (</>) used for parenthesis (an inserted explanation or afterthought), hence why we also use that alternative name. These angled brackets eventually rounded [(/)] whereby they were first termed as ‘lunulae’ by Erasmus for taking on the appearance of moons. The later term ‘bracket’ in fact comes from a Germanic root that is shared with the English word ‘brace’. Other forms of brackets such as square brackets ([/]) and curly brackets ({/}) are simply variations of the original round brackets.³⁵

Quotation Marks

Quotation marks have their origin in Ancient Greek, where writers would often incorporate a diple symbol (> (left), < (right), often with added dots or strokes) in the margins of a text to highlight certain distinctions. Isodore of Seville gives us the example of Homer using them to distinguish between Mount Olympus and the heavenly Olympus.³⁶ By the Middle Ages, they were used to highlight important sections of a text and were used on both ends of the line instead of just one or the other. They < gradually moved to either side of the specific quote itself > rather than the whole line, and came to be associated with direct speech. With the invention of the printing press, virgulae commas (‘/’ or “/”) were often used in the place of the angled brackets which then shortened into ('/'), and then into different variations such as the double quotation marks ("/").³⁷ Different countries later adopted their own variations. For example some European languages such as German use one lower and one higher („/“), while, French, Greek and Cyrillic have opted for (double) chevrons («/») rather than commas.

Watch: Why Did People Start Using Punctuation? | Today I Found Out

Click here →

Non-Western variants

Today, many non-Western scripts have adopted Latin punctuation, especially those from countries colonised by the Europeans. Many have, however, resisted the temptation and maintained their own indigenous systems. Two notable examples are Ge’ez and Armenian.³⁸ ³⁹

Punctuation in the East

Brahmic scripts, being phonetic, developed their own set of punctuation marks that have now mostly been replaced by Latin punctuation in everyday writing. Some examples from Devanagari include the avagraha (ऽ) used to indicate vowel elision (much like an apostrophe)⁴⁰, the danda (“bar”) (।) to end a sentence (like a full stop), and the double danda (॥) to end a full verse.⁴¹ ⁴²

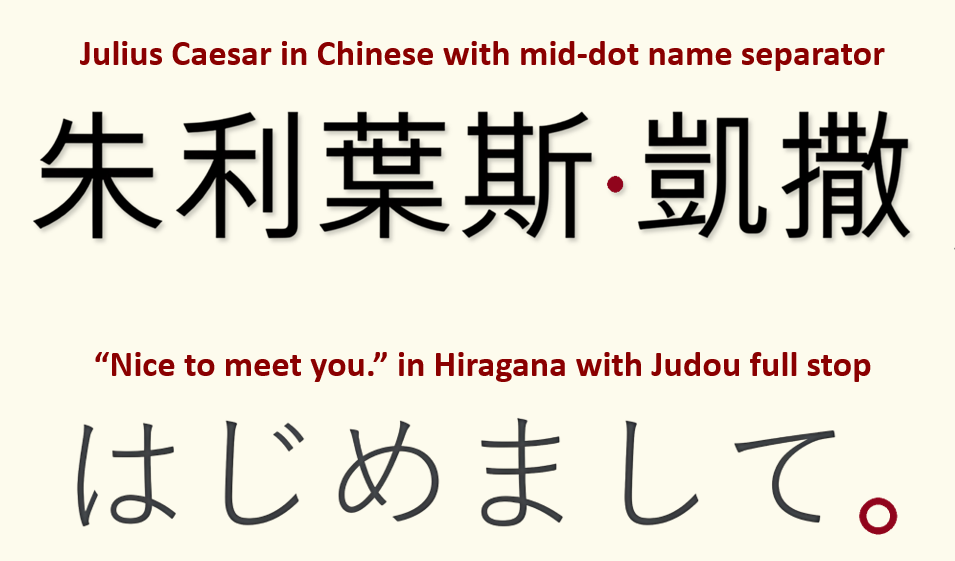

While Chinese doesn’t use punctuation marks to the same extent as phonetic scripts, it did develop its own punctuation system centuries ago known as jùdòu (句读). For example, the centred dot (·) is still used to mark phonetic divisions within words and separate first and last names translated from foreign languages. Special marks were used to indicate a stop such as () or (), or simply a blank space. Otherwise, the special characters 夫, 维, 且, and 盖 could be used as sentence-beginning particles (similar to English discourse markers like "now... or "firstly..."). Similarly, characters such as 兮, 也 or 矣 could be used as sentence-ending particles. Today, Chinese and Japanese use the jùdòu mark () as a full stop, and () as a comma (to separate items in a list only). Japanese and traditional Chinese use double and single rectangle quotation marks (/) (horizontal), but simplified Chinese has imported the Latin variant (“ ”).⁴³ ⁴⁴ Korean now mostly uses Latin commas for quotations, but traditionally used angled brackets (/) for titles and headings.⁴⁵

Other symbols

The ampersand

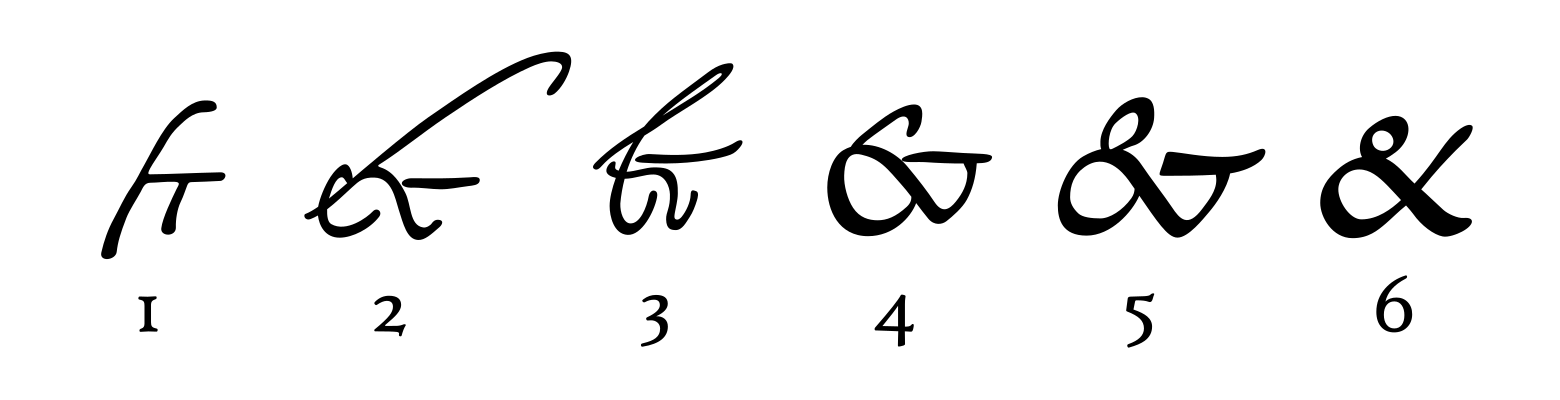

Other symbols such as the ampersand (&) also have interesting histories. The ampersand evolved from a ligature of the letters E & T in the Latin word ‘et’ (‘and’) from the 1st century CE. It became more and more stylised over time before settling in its present form (&).⁴⁶

The percent symbol

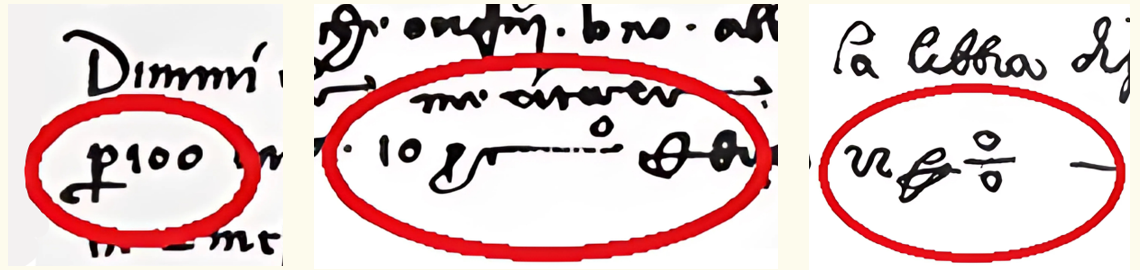

Before the 15th century, no percent symbol existed. Many people believe it evolved from a rearrangement of the digits in 100. But in fact, it most likely evolved from the Italian phrase “per cento” (“by the hundred”) which medieval merchants often abbreviated as ‘per 100’, ‘p 100’ or ‘pc’. When written as ‘p 100’, a horizontal line was often written below the 'p' to indicate an abbreviation. When written as ‘pc’, the letters began to be connected by a running loop extending from the ‘p’, and the ‘c’ began to resemble more of an ‘o’. At some point, authors also started writing a small ‘o’ at the end of this loop which was common for writing Italian ordinals (similar to English ‘-th’) and the ‘pc’ started resembling a fraction sign. Eventually the ‘p’ disappeared altogether, leaving just a symbol like this (). The sign eventually tilted to give us the current percent symbol (%). It was standardized through printing in the 19th century and widely adopted in finance, taxation, and everyday use by the 20th century.⁴⁷

The hash sign

The symbol is thought to have originated from ‘lb’, an abbreviation of the Roman phrase libra pondo meaning “pound weight” (hence why the sign is referred to as the ‘pound sign’ in North America). The abbreviation “lb” was originally represented as a ligature (℔), with a horizontal line through it to indicate it was shortened. Over time, this symbol was simplified, evolving into the familiar form (#) of two horizontal strokes (=) crossing through two slanted lines (//) and used to denote numbers more generally.⁴⁸

The ‘at’ symbol

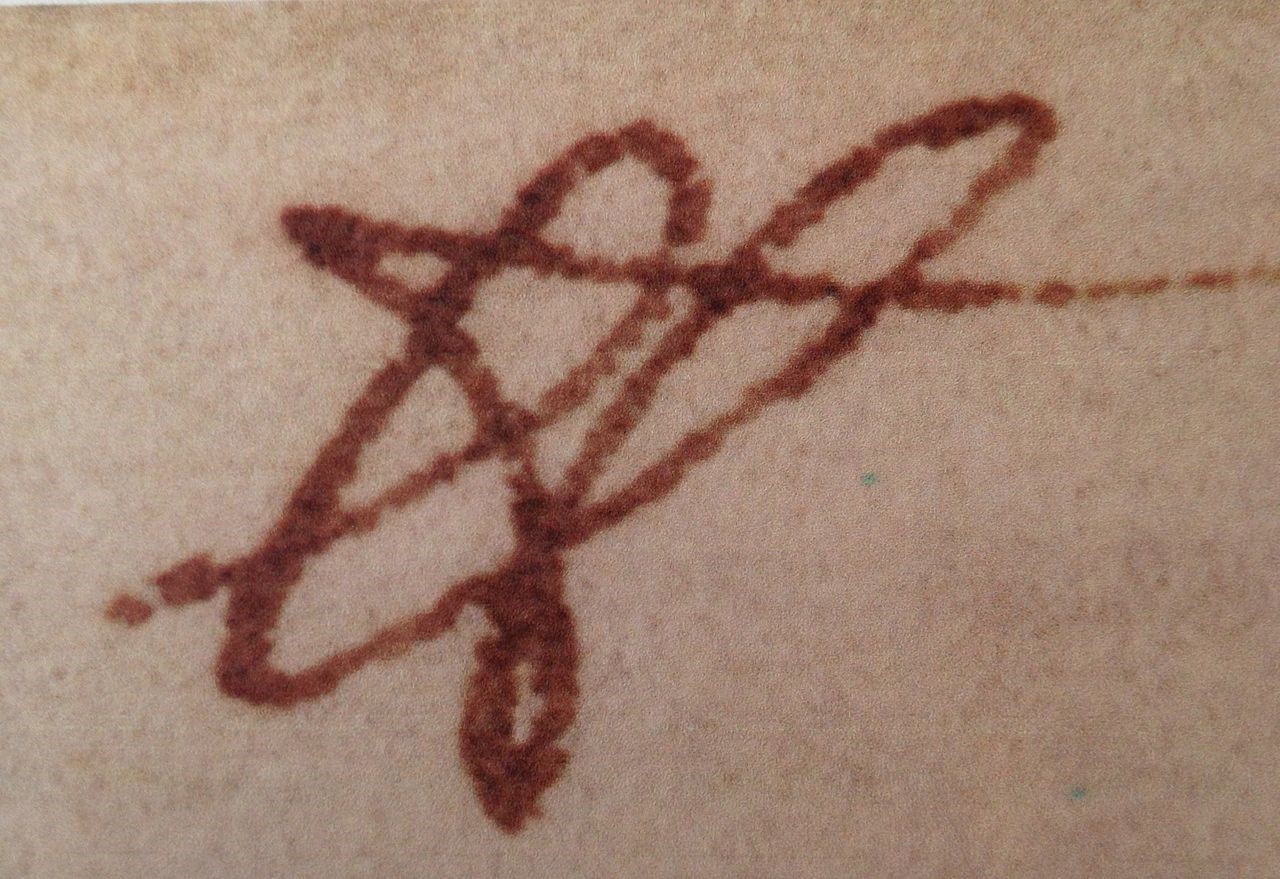

The ‘at’ symbol (@) is widely attributed to computer engineer Ray Tomlinson, who implemented the first localised email system in 1971. He needed a symbol to attach names to computers. But use of the symbol far precedes Tomlinson. It was first used in Southern European countries for the word arroba, a cognate with the Latin amphora. Amphora was the unit for measuring volume in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds and referred to a jug with two handles. The Spanish and Portuguese, however, used the symbol as a shorthand for a measure of weight, rather than volume. Over time, other European languages started using the symbol as a shorthand for any unit of measure for commercial purposes. In the mid-1800s, the symbol was included in some early models of the typecast typewriter and then found its way onto early digital keyboards in the mid-20th century called teletypes. In 1971, Tomlinson simply had to look down at his teletype to find the symbol he needed.⁴⁹

Asterisk

Some have falsely drawn connections between the modern asterisk (*) and the star-like cuneiform determinative dingir (𒀭), but there is no evidence to suggest a connection there. A much more likely explanation is the Greek asteriskos (※), a symbol used by Aristarchus of Samothrace more than two thousand years ago. It was employed to indicate duplicated lines while proofreading Homeric poetry. Origen of Alexandria later adopted this symbol in his Hexapla to denote missing Hebrew lines in biblical texts. While the appearance of the asterisk changed over time, its primary function as a mark for identifying textual errors persisted. During the Middle Ages, the asterisk was often used to highlight specific sections of a text, typically connecting them to notes or comments in the margins. Today the asterisk resembles a star (*).⁵⁰

The Arrow

Before the wide use of the modern arrow symbol, a pointing finger (known as a manicule) (☞) was often used to draw the reader’s attention to important text or to give direction on signs. In the 18th century, writers started using an archer’s arrow (➵) to indicate direction from the perspective of the reader. Over time the archer’s arrow was simplified and abstracted, eventually losing its fletching and coming to resemble the modern arrow symbol (→).⁵¹

Mathematical symbols

For most of history, mathematical functions were mostly expressed in words (e.g. “and…” or “less…”). In fact, it wasn’t until the 16th-17th centuries that the mathematical symbols that we are so familiar with today began to emerge. A number of such symbols were simply appropriated Latin or Greek letters (think ‘e’ or ‘π’). Why these letters were used is another story. But during this period a range of new symbols also emerged. The plus sign (+) for example, comes from et the Latin for 'and', eventually losing the ‘e’. The minus sign (-) meanwhile is one symbol that does have an ancient history, used by Egyptian and Greek mathematicians, but only gaining popularity in Europe in the 1600s. The equals sign (=) was invented by a Welsh mathematician claiming that two parallel lines was the perfect representation of equality. An English mathematician invented the multiplication sign (x), replacing the previously used mid-dot (·). The division sign (÷) was introduced by a Swiss mathematician to denote a fraction and based on the obelus (÷) originally used for text annotation. Another Englishman, introduced the infinity symbol ( as a logical representation of the "never-ending". The square root (or radical) sign (√) was used by Europeans by the 16th century. Its origin is speculative, but may derive from the ‘r’ in the Latin word radix (root). Another theory is that it derives from the Arabic letter jīm in its initial form (ﺟ) placed over a number, the first letter of the Arabic word for root – جذر (jaḏr).⁵² ⁵³

Watch: Where do math symbols come from? | John David Walters - Teded

Correction Symbols

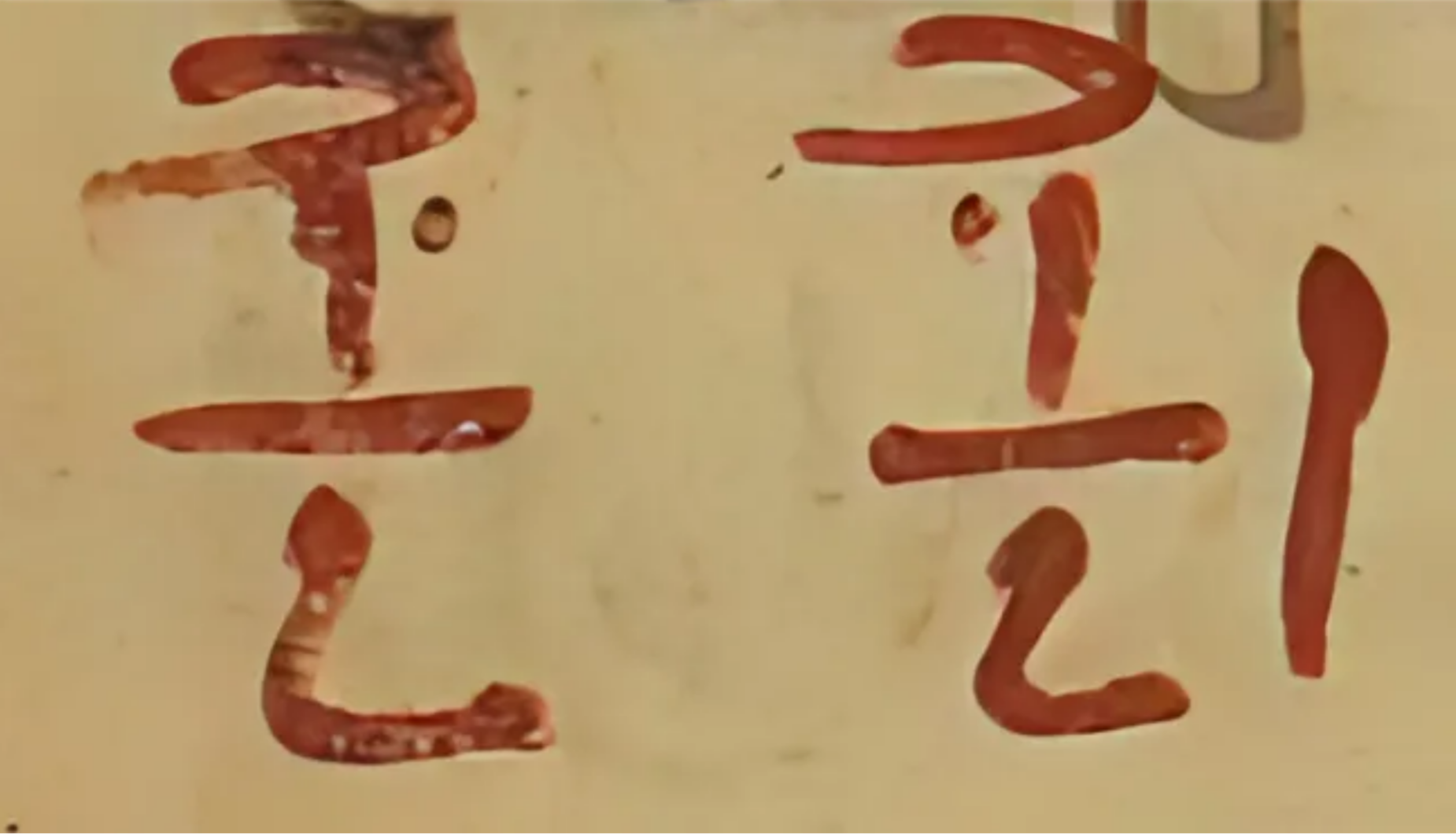

The modern tick (UK) or check mark (US) (✓) can be used in English to indicate something correct or complete, or a selection within a box (☑). An [X] often denotes that something is incorrect or to make a selection within a box (☒). The [X] had been used by medieval scribes to highlight the location of an error, much like the asterisk, while the tick is believed to derive from the Latin word veritas (truth). According to this theory, scribes would often write “V” next to entries to indicate that a statement was accurate. Over time, the right arm of the [V] became longer than the left, resembling the modern tick (✓).⁵⁴ Many languages that don’t use the Latin script follow this “English” convention, but interestingly, many European languages that do use the Latin script use the symbols in different ways. For example, in Swedish the tick is used to indicate that something is incorrect and an [R] (standing for rätt (correct). In Finnish, the tick also indicates incorrect resembling the [V] from the word väärin (incorrect).⁵⁵ In the Netherlands and former Dutch colonies, a ‘(goedkeurings)krul’ (approval curl) or ‘flourish of approval’ in English () can be used to indicate agreement or approval. It possibly derives from the letter G standing for goed (good).⁵⁶ In German, the tick is used to indicate correct, but an [f] for falsch (false) is often used to indicate incorrect.⁵⁷ China follows the English conventions, but Japan and Korea use a circle (〇) for correct and a tick (✓) or slash (/) for incorrect, as well as a triangle (△) for partially correct.⁵⁸ A tick (✓) can also sometimes be used to make a selection on a form and an [X] to denote “not selected”. This is the supposedly the origin of the Playstation controller buttons, with the square (☐) denoting a piece of paper.⁵⁹

Diacritics

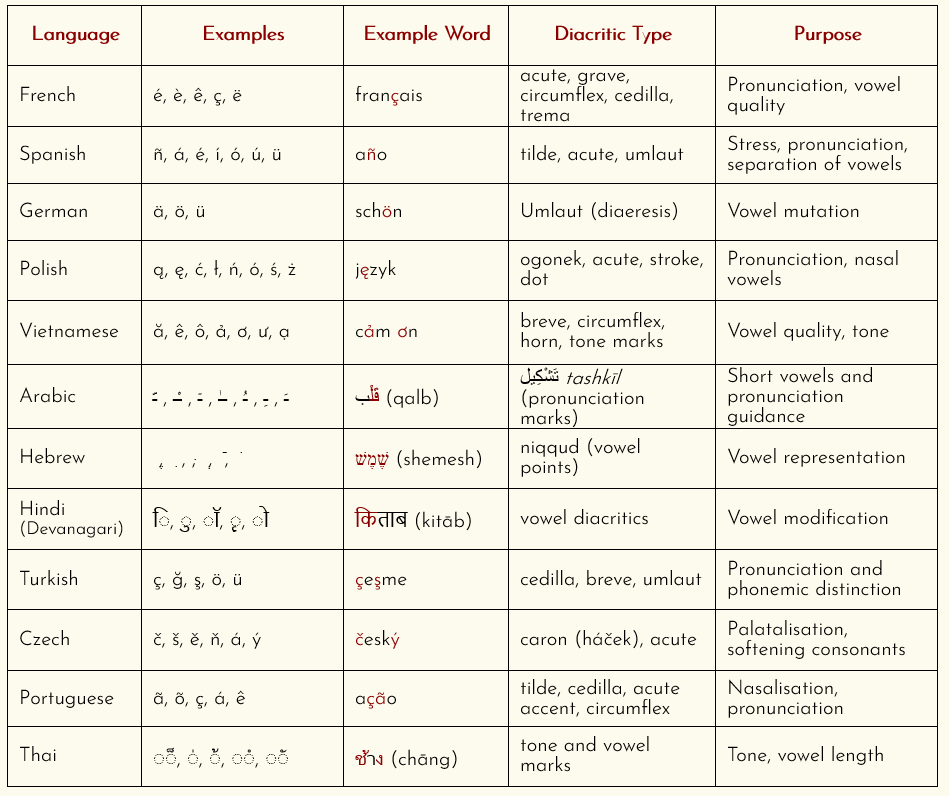

Diacritics are marks added to letters in many languages around the world to indicate vowels (in the case of abugidas) or to indicate pronunciation.

Diacritics in the form of accents were used as far back as Ancient Greece with Aristophanes of Byzantium simplifying the system in the 3rd century BCE. Diacritics indicate things like stress, tone, or vowel quality, and are today found in both alphabetic and syllabic writing systems. While some languages use them only occasionally, others rely on them heavily to distinguish their phonology. They can come in the form of accents (◌́, ◌̀), cedillas (◌̧), tildes (◌̃), circumflexes (◌̂), umlauts (◌̈), breves (◌̆) and a host of other lines, dots and curls. Though small, these marks play an important role in communicating clear pronunciation and intonation.⁶⁰

In some languages, notably abugidas, diacritics are built into letter formation to discern vowels rather than being used as separate symbols. For example, in Malayalam (in Indic abugida), പ /pa/, പി /pi/, പു /pu/, പെ /pe/, പൊ /po/.

Continue to Chapter 9 →

Glossary of terms

Chapter 8

Ampersand: a symbol (&) representing the word “and”, derived from the Latin et

Amphora: an ancient jar with two handles, used as a unit of volume in inscriptions

Asterisk: from Greek asteriskos (“little star”), a symbol (*) used to mark a footnote or omission

Apostrophe: from Greek apostrophos (“turning away”), a punctuation mark indicating omission or possession

Avagraha: a Sanskrit symbol (ऽ) used in Indian scripts to indicate prodelision or prolongation

Capitulum: Latin for “little head”, a symbol or heading mark indicating the start of a chapter or section

Chevron: a V-shaped mark used in writing

Danda: a punctuation mark (|) used in South Asian scripts to indicate the end of a sentence or verse

Determinative: a non-phonetic symbol added to a word to clarify its meaning or category (e.g., action, object, person)

Diacritic: a mark added to a letter to alter its pronunciation or meaning

Diple: Greek for “double”, a mark resembling (>) used in ancient texts to highlight noteworthy passages

Enotikon: from Greek enotikon (“unifying”), a mark () used to indicate that two words should be read as one

Flourish of approval: a decorative mark added to manuscripts to indicate approval or correctness

Hedera: from Latin hedera (“ivy”), a decorative punctuation mark shaped like an ivy leaf, used to divide text

Hypodiastole: from Greek hypo- (“under”) and diastole (“separation”), a punctuation mark () used to separate words or clarify meaning

Interpunct: from Latin inter (“between”) and punctum (“point”), a small dot used as a word separator

Judou mark: Chinese punctuation marks used to mark partitions in a text

Kolon: Greek for “member” or “clause”, a rhetorical or syntactic unit, sometimes marked in ancient writing

Komma: Greek for (“I cut”), a short phrase or segment of a sentence

Ligature: a single character formed by joining two or more letters

Libra pondo: Latin for “pound by weight”, origin of the abbreviation “lb”

Majuscule: from Latin maiusculus (“rather large”), large or uppercase letter forms

Manicule: from Latin manicula (“little hand”), a pointing hand symbol (☞) used to draw attention to text

Minuscule: from Latin minusculus (“rather small”), small or lowercase letter forms

Obelus: from Greek obelos (“spit” or “sharp stick”), a symbol (÷ or †) used to indicate doubtful or spurious text

Ordinal: a number indicating position or order (e.g., 1st, 2nd), sometimes marked with a superscript suffix

Paragraphos: Greek for “written beside”, a mark used in ancient texts to indicate a new section

Parenthesis: Greek for “insertion”, marks used to enclose additional or explanatory material

Particle: a short word or grammatical element with functional rather than lexical meaning

Periodos: Greek for “go around”, a complete sentence or rhetorical unit

Pilcrow: a symbol (¶) marking the start of a paragraph

Punctus: Latin for “point”, a generic term for dot-based punctuation marks

Radix: Latin for “root”, the base or foundational part of a number or character

Scriptio continua: Latin for “continuous writing”, a style of writing without spaces or punctuation

Teletype: a telecommunication device that prints text sent over wires or radio

Veritas: Latin for “truth”, often used symbolically in seals, inscriptions, or mottoes

Virgula: Latin for “little rod”, a small slash (/) or line used in punctuation or as a diacritic

Word separator: any symbol, space, or mark used to distinguish words in writing

Useful Links

Encyclopedia of Math – Mathematical Symbols: https://encyclopediaofmath.org/wiki/Mathematical_symbols#Ancient_Greece

Merriam-Webster – A Guide to Deciphering Diacritics: https://www.merriam-webster.com/grammar/how-to-use-and-understand-diacritics-diacritical-marks

Shady Characters by Keith Houston (origins of punctuation): https://shadycharacters.co.uk/

Footnotes

Chapter 8

1. Keith Houston, ‘The Mysterious Origins of Punctuation’, BBC, <https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150902-the-mysterious-origins-of-punctuation> [accessed April 2025]

2. Thomas Christiansen et al, ‘Insights Into the Composition of Ancient Egyptian Red and Black Inks on Papyri Achieved by Synchrotron-Based Microanalyses’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 45, 2020, p. 27286 <https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004534117>

3. Keith Houston, ‘The Mysterious Origins of Punctuation’, BBC, <https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150902-the-mysterious-origins-of-punctuation> [accessed April 2025]

4. Ellen Lupton, Period Styles: A Brief History of Punctuation, The Herb Lubalin Study Center, Cooper Union, 1988

5. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, The World’s Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, 1996, pp. 53, 77, 92, 121, 135, 801

6. ‘Aramaic Punctuation Marks’, Wiktionary, <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Category:Aramaic_punctuation_marks> [accessed April 2025]

7. ‘Syriac Punctuation and Signs’, Unicode, <https://www.unicode.org/charts/nameslist/n_0700.html> [accessed April 2025]

8. Ross Nichols, ‘Rightly Dividing the Words – The Shapira Manuscripts as the Earliest Witness to Word Separation in a Biblical Manuscript’, The Moses Scroll, 28 April 2021, <https://themosesscroll.com/rightly-dividing-words-the-shapira-manuscripts-as-the-earliest-witness-to-word-separation-in-a-biblical-text/> [accessed April 2025]

9. ‘Notes on Ethiopic Localization’, Abyssinia Gateway, <http://www.abyssiniagateway.net/fidel/l10n/> [accessed April 2025]

10. Paul Saenger, Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading, Stanford University Press, 1997, pp. 9-10

11. Fig. 8.5: @Arkony, Paragraphos, Wikimedia Commons, <https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/74/Paragraphos.png> [CC BY-SA 4.0, viewed April 2025]

12. ‘Punctuation Shared with Latin’, Opoudjis, <https://opoudjis.net/unicode/punctuation.html> [accessed April 2025]

13. Paul Saenger, Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading, Stanford University Press, 1997, p. 10

14. ‘Rare Punctuation Marks Can Be Fun’, The Secret Professor, <https://thesecretprofessor.com/rare-punctuation-marks-can-be-fun/> [accessed April 2025]

15. ‘Hedera Punctuation Mark: What Is It & How To Use It?’, Grammar Lookup, <https://www.grammarlookup.com/hedera-punctuation-mark/> [accessed April 2025]

16. Steph Koyfman, ‘What’s the Deal with French Spacing?’, Babbel, 31 May 2022, < https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/french-spacing> [accessed May 2025]

17. Paul Saenger, Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading, Stanford University Press, 1997, pp 12-13

18. Bård Borch Michalsen, Signs of Civilisation: How Punctuation Changed History, Hodder & Stoughton, 2019

19. Ellen Lupton, Period Styles: A Brief History of Punctuation, The Herb Lubalin Study Center, Cooper Union, 1988

20. Isodore of Seville, Etymologies, (English Translation by Stephen Barnsey et al), Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 50

21. ‘Punctus Elevatus’, Wiktionary, <https:/en.wiktionary.org/wiki/punctus_elevatus> [accessed May 2025]

22. ‘Punctus Versus’, Wiktionary, <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/punctus_versus> [accessed May 2025]

23. ‘How to Read Medieval Handwriting (Paleography)’, Harvard, <https://web.archive.org/web/20160414142106/http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic453618.files/Central/editions/paleo.html> [accessed April 2025]

24. ‘Reading Before Punctuation’, Haverford, <https://web.archive.org/web/20060902185038/http://www.haverford.edu/classics/courses/2006S/lat101/handouts/no_spaces_aeneid.pdf> [accessed April 2025]

25. Steph Koyfman, ‘What’s the Deal with French Spacing?’, Babbel, 31 May 2022, < https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/french-spacing> [accessed May 2025]

26. Keith Houston, ‘The Mysterious Origins of Punctuation’, BBC, <https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20150902-the-mysterious-origins-of-punctuation> [accessed April 2025]

27. Dave Child, ‘The Fall of the Semicolon: Punctuation Evolving‘ Readable, <https://readable.com/blog/the-fall-of-the-semicolon-punctuation-evolving/> [accessed April 2025]

28. David Crystal, Making a Point: The Pernickety Story of English Punctuation, Profile Books, 2015, p. 25

29. ‘The History of the Question Mark’, Historically Irrelevant, <https://historicallyirrelevant.com/post/3708038709/the-history-of-the-question-mark> [accessed April 2025]

30. Simon Ager, ‘Armenian’, Omniglot, <https://www.omniglot.com/writing/armenian> [accessed April 2025]

31. Eric Partridge, You Have a Point There: A Guide to Punctuation and its Allies, Routledge, 1953, p. 82

32. Keith Houston, Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, pp. 121-124

33. idlib, p. 122

34. ‘… dot, dot, dot: How the Ellipsis Made its Mark’, 21 October 2015, Cambridge University, <https://www.cam.ac.uk/

35. Lynne Truss, Eats, Shoots and Leaves, Thorndike Press, 2004, p. 180

36. Isodore of Seville, Etymologies, (English Translation by Stephen Barnsey, et al), Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 51

37. Keith Houston, ‘The Long and Fascinating History of Quotation Marks‘, Slate, <https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/01/quotation-marks-long-and-fascinating-history-includes-arrows-diples-and-inverted-commas.html> [accessed April 2025]

38. ‘Notes on Ethiopic Localization’, Abyssinia Gateway, <http://www.abyssiniagateway.net/fidel/l10n/> [accessed April 2025]

39. Ager, Simon, ‘Armenian’, Omniglot, <https://www.omniglot.com/writing/armenian> [accessed April 2025]

40. ‘Avagraha’, Wiktionary, <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/avagraha> [accessed April 2025]

41. ‘Danda’, Wiktionary, <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/danda#English> [accessed April 2025]

42. ‘Double Danda’, Wiktionary, <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/double_danda> [accessed April 2025]

43. ‘A Table of Chinese Punctuation Marks’, Tuttle Publishing, <https://www.tuttlepublishing.com/content/docs/9780804840163/Ref%20PDFs/RefA.pdf> [accessed April 2025]

44. Sun Jiahui, ‘How China Adopted Western Punctuation’, The World of Chinese, <https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2021/09/how-china-adopted-western-punctuation/> [accessed April 2025]

45. Lead In Seo Chang Education Centre, ‘Learn How to Write a Manuscript’, The Young Writer’s Secret Garden, <https://m.blog.naver.com/yanagi/223451438932> [accessed May 2025]

46. Keith Houston, Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, pp. 59-66

47. David Euguene Smith, Rara Arithmetica, Boston Ginn, 1908, pp. 439-441

48. Keith Houston, Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, pp 41-42

49. Keith Houston, ‘The At Symbol’, Shady Characters, 24 July 2011, <https://shadycharacters.co.uk/series/the-at-symbol/>

50. Keith Houston, Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, pp. 97-105

51. Robert J. Finkel, ‘History of the Arrow’, Printing History, 1 April 2015, <https://printinghistory.org/arrow/> [accessed April 2025]

52. Labh, Sunny, ‘Tracing the Origins of Mathematical Symbols’, Cantors Paradise, 22 April 2023, <https://www.cantorsparadise.com/tracing-the-origins-of-mathematical-symbols-%CF%80-%CF%83-f-x-16e7868ee2a2> [accessed April 2025]

53. Jeffrey A. Oaks, ‘Algebraic Symbolism in Medieval Arabic Algebra’, Philosophica, vol. 87, 2012, <http://dx.doi.org/10.21825/philosophica.82139>, p. 37

54. Pulse Studio, ‘Checkmark: The Origins of a Revolution’, Medium, <https://medium.com/@pulsestudio/checkmark-the-origins-of-a-revolution-b4d5f2b2926d> [accessed April 2025]

55. ‘General Punctuation’, Unicode, <https://www.unicode.org/reports/tr28/tr28-3.html#6_1_general_punctuation> [accessed April 2025]

56. Katja Keuchenius, ‘Waar Komt Het Krulletje Vandaan?’, NRC, <https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2011/02/09/waar-komt-het-en-vandaan-het-11995186-a946165> [accessed April 2025]

57. Thorsten Henke, ‘Korrekturzeichen und Verständliche Randkommentare in Klausuren‘, Friedrich Verlag, <https://www.friedrich-verlag.de/friedrich-plus/sekundarstufe/deutsch/grammatik/deutschunterricht-korrekturzeichen-und-randkommentare/> [accessed April 2025]

58. ‘How Teacher’s Mark Answers in Japan’, Japanese Creations, <https://blog.japanesecreations.com/how-teachers-mark-answers-in-japan> [accessed April 2025]

59. Poppy, Bilderbeck, ‘Playstation Buttons: What They Actually Mean’, Uni Lad, <https://www.unilad.com/gaming/news/playstation-buttons-what-they-actually-mean-realization-095964-20241205> [accessed April 2025]

60. ‘Diacritic’, Encyclopædia Britannica, <https://www.britannica.com/topic/diacritic> [accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.1: Edwin Smith Papyrus, illustration by Jeff Dahl, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edwin_Smith_Papyrus_v2.jpg> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.2: Latin in scriptio continua, (image cropped), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Great_Library_of_Alexandria,_O._Von_Corven,_19th_century.jpg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.3: Jin Zhang, Chinese text (1909), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jin_Zhang_Chinese_calligraphy,_one_hundred_images_of_goldfish,_1909.jpg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.4: 17th century Syriac liturgical text, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Syriac_NT_Lectionary,_Borgia_Syriac_Ms_13.jpg> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.5: @Arkony, Paragraphos, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paragraphos.svg> [CC BY-SA 4.0, viewed April 2025]

Fig. 8.6: Menander’s Sicyonians, illustration by @Zunkir, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Menandre_Sycioniens_Medinet_Ghoran_2272e.jpg> [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Fig. 8.7: Appius Claudius, (colour enhanced), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Appiuscaecusstele01.jpg> [CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.8: Boriska, ‘Fust-Schöffer Bible’ (1462), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sch%C3%B6ffer-Fust_Biblia.jpg> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.9: Aristotle, ‘Physics’, (image cropped, rings added), Wikimedia Commons, < https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aristotle_latin_manuscript.jpg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.10: O. Von Corven, ‘Ancient Library of Alexandria’, illustration by Igor Merit Santos, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Great_Library_of_Alexandria,_O._Von_Corven,_19th_century.jpg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.11: Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, ‘Saint Isidor of Sevilla’ (1655), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Isidor_von_Sevilla.jpeg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.12: David Schrader, ‘Evolution of the Period (Full Stop), Colon and Comma’ (© author’s own, 2025)

Fig. 8.13: @Angelus, development of the question mark, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quaestio.svg> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.14: 8th century punctus interrogativus, (ring added), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Btv1b6000718s.png> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.15: ‘Punctus Interrogativus from Bern’, (ring added), illustration by E-Codices, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Punctus_interrogativus_from_Bern,_B%C3%BCrgerbibliothek_Cod._162,_f._15r.jpg> [CC BY 3.0, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.16: dagger symbol for footnote, (ring added), in John Bunyan, , 1678 , illustration by Early Novels Database, Flickr, <https://www.flickr.com/photos/97741188@N04/14489825415> [CC BY 2.0, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.17: David Schrader, Original Use of the Enotikon’ (© author’s own, 2025) based on information from ‘Punctuation Shared with Latin’, , <https://opoudjis.net/unicode/punctuation.html> [accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.18: Diple variants, (background removed), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diple-periestigmene.png> [CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.19: Codex Fuldensis, (red rings added), Wikipedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Start_of_the_prologue_to_Acts_from_the_Codex_Fuldensis.png> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.20: @Alatius, evolution of the ampersand, Wikimedia Commons, <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Historical_ampersand_evolution.svg> [CC BY-SA 3.0, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.21: historical percentage symbols, in David Euguene Smith, , Boston Ginn, 1908, pp. 439-441, sourced from Wikipedia, <https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Percent_sign_in_1648.png> [public domain, accessed April 2025], Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Percent_sign_in_1339.png> [public domain, accessed April 2025], Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Percent_sign_in_1425.png> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.22: Isaac Newton, lb ligature, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Libra_pondo_abbreviation_newton.jpg> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.23: Castilian aroba, (image enhanced), illustration by Jorge Romance, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ariza1448-2.jpg> [GNU free documentation license, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.24: Asterisks from 4th-5th century Greek text, (rings added), Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Asteriskos.gif> [public domain, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.25: Wanted poster of John Wilkes Booth (1865), (image cropped, ring added), Wikipedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:John_Wilkes_Booth_wanted_poster_new.jpg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.26: Fryderyk Bernard Wernher, Głogów castle, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Glogau_zamek_XVIII_wiek.jpg> [public domain, accessed May 2025]

Fig. 8.27: Arabic use of jīm as square root symbol, (image enhanced), in Jeffrey A. Oaks, Algebraic Symbolism in Medieval Arabic Algebra, vol. 87, 2012, <http://dx.doi.org/10.21825/philosophica.82139>, p. 37

Fig. 8.28: Goedkeuringskrul, (background removed), in ‘The Dutch “Krul” – A Unique Mark of Approval’, Transparent, <https://blogs.transparent.com/dutch/the-dutch-krul-a-unique-mark-of-approval/> [©, accessed April 2025]

Fig. 8.29: David Schrader, ‘Korean correction markings’, (©, author’s own, 2025)

Share this page

To the

Top

To the

Bottom